The Numbers Behind Small Loans

The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1700 B.C.E.) is one of the earliest known legal texts. It contains the first known formulation of lex talonis, the principle of exact retaliation. Today people are most familiar with its Biblical version: an eye for an eye.

The Code of Hammurabi is also the first known attempt of a regulator to cap lending interest rates:

If a merchant lends grain at interest, for one gur he shall receive one hundred sila as interest (33 percent); if he lends money at interest, for one shekel of silver he shall receive one-fifth of a shekel as interest (20 percent).

The first recorded interest rate cap happened at the same time as the principle of reciprocal justice was established. Since ancient times people have wanted to borrow money. Rulers, whether Babylonian kings or Washington bureaucrats, have felt the need to cap the interest rates at which people can borrow from each other, as they fear that lenders can exploit borrowers with immoral interest rates.

But this isn’t a discussion about the moral question of small loans. I’ve written about the topic elsewhere. Rather, this is an attempt to establish some numbers and facts with regards to small loans. And when discussing the subject, regulation is a key part.

What are small consumer loans?

Small consumer loans are short duration loans (<12 months) for relatively small amounts given to individuals. These loans can be either unsecured (in the case of most credit cards, bank overdrafts or payday lenders) or secured (in the case of secured credit cards or pawnbrokers).

Most of the figures I’ll share come from a 2015 government review of the UK payday loan industry. In wealthy countries, these numbers will be within the same order of magnitude. However, the actual distribution of loan duration and values depends on the market, credit product structure, and customer type.

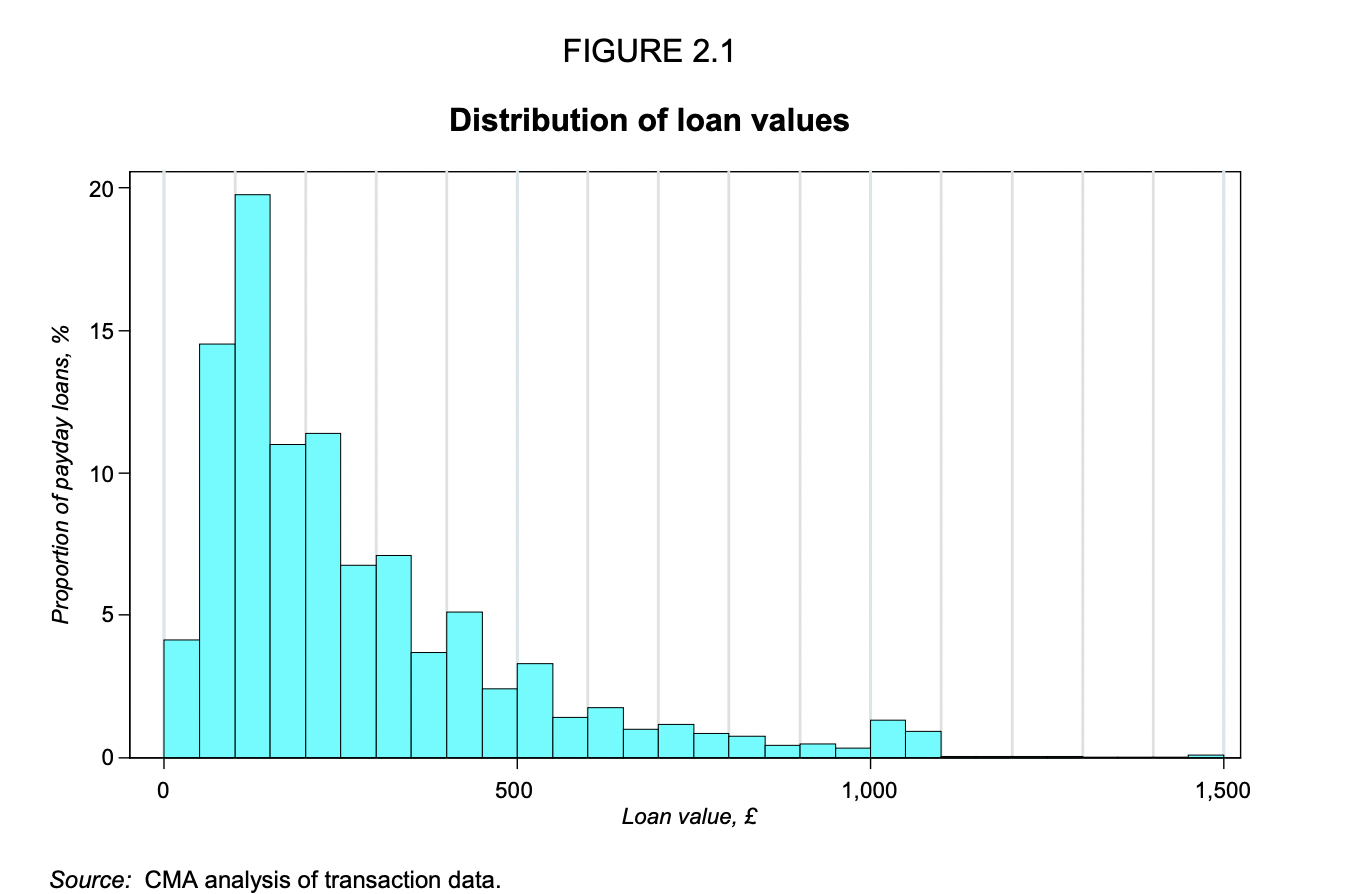

In the UK, the mean payday loan size was about £260 (330 USD) with the median being around £200 (250 USD). The distribution can be seen below:

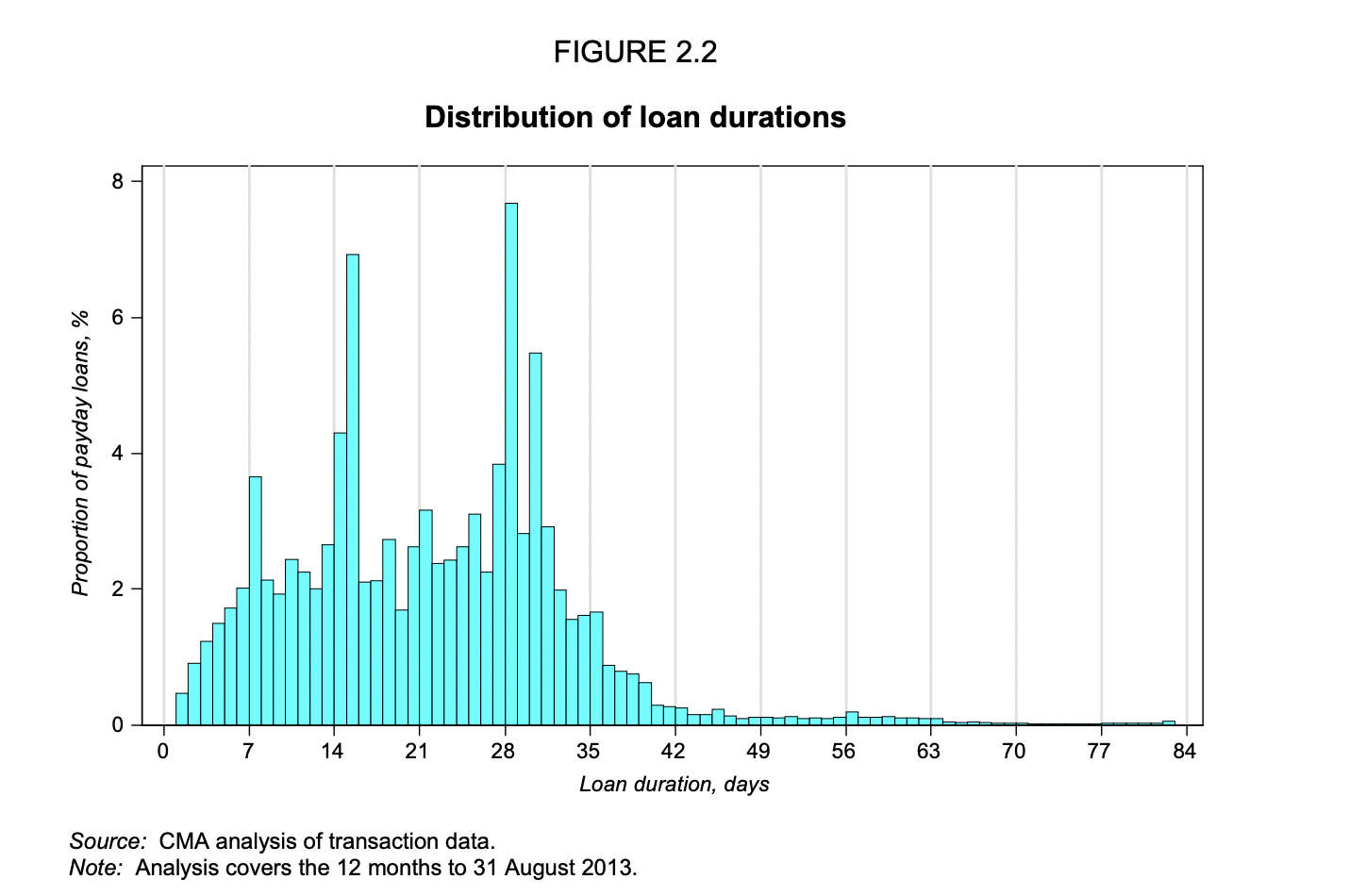

The same review found that while some products offer loans up to a year, the overwhelming majority of them (80%) are to be repaid within 31 days. Excluding the small minority of loans of 12 months or more, the average duration was 22 days.

Why do people take out small consumer loans?

Most people take out small loans to cover general living expenses, such as groceries or utility bills, often due to unexpected increases in expenses or decreases in income.

Most of these customers do not have access to traditional credit facilities. This can be because they have no credit history (they are young or undocumented) or because they have experienced credit or financial problems in the past. Many of them have a bad credit rating, have experienced county court judgements against them or have been visited by a bailiff.

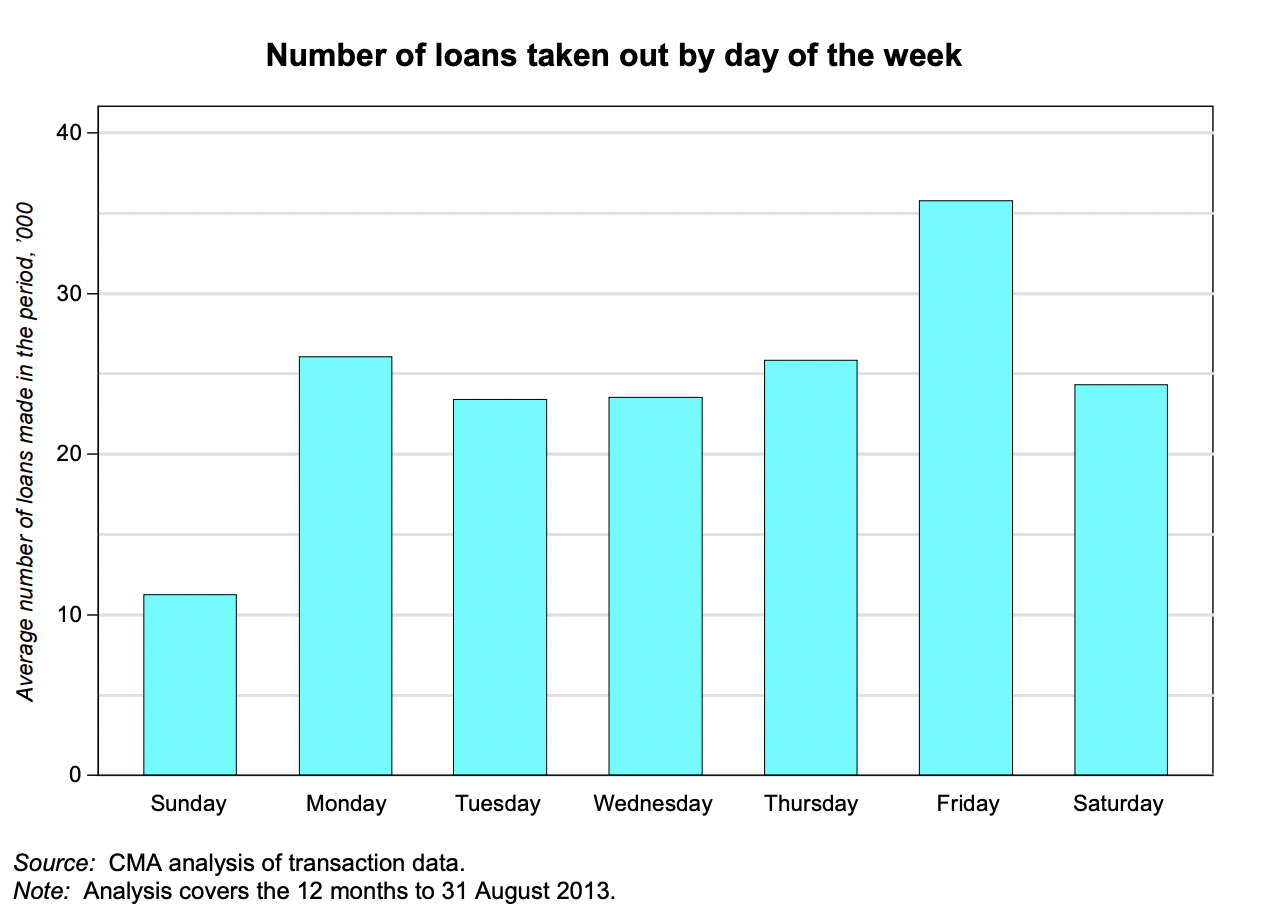

The timing of when people take out small loans is also a good indicator of their reasons for doing so. In other words, people borrow when they expect to be cash-strapped: before payday, a weekend or a period with lots of expenses.There is a strong seasonal trend in taking out loans at the beginning (or end) of the month. Within the week, Fridays are the busiest day for originations. Generally September and December are high demand months, when the start of school and the Christmas holidays place a burden on the consumers’ finances.

Why do people repeatedly take out small consumer loans?

Another interesting seasonal pattern is that clients tend to borrow more just after their payday than before their payday. This could be due to irregular income (i.e. you get paid less than you were expecting). But it is most likely due to credit cycling: customers use their income to pay off their debts and take out new debts.

The typical customer will take out multiple loans a year. In fact, around three-quarters of customers take out more than one loan in a year, and that on average a customer takes out around six loans per year. Repeat custom typically accounts for a large proportion of lenders’ business. More than 80% of all loans issued by UK payday lenders in 2012 were made to customers who had previously borrowed from the lender.

The question of customers repeatedly taking out loans is a sensitive one. Just as most B2C businesses rely on recurring customers, lenders consider repeat customers fundamental to their operations. In fact, lenders often lose money on the first loan issued to individuals, as the origination costs and delinquency rates are much higher than for any subsequent transaction. On the other hand, the high rates of customers repeatedly taking out loans dispel the notion that these small loans are taken out by customers due to unexpected changes in financial circumstances.

Customers repeatedly taking out expensive loans sounds a lot like a debt cycle to consumer advocates and regulators. Consumers can get stuck in a cycle where an increasing proportion of their income goes towards paying credit expenses. These costs can be prohibitive, because small loans are not cheap.

Why are small consumer loans expensive?

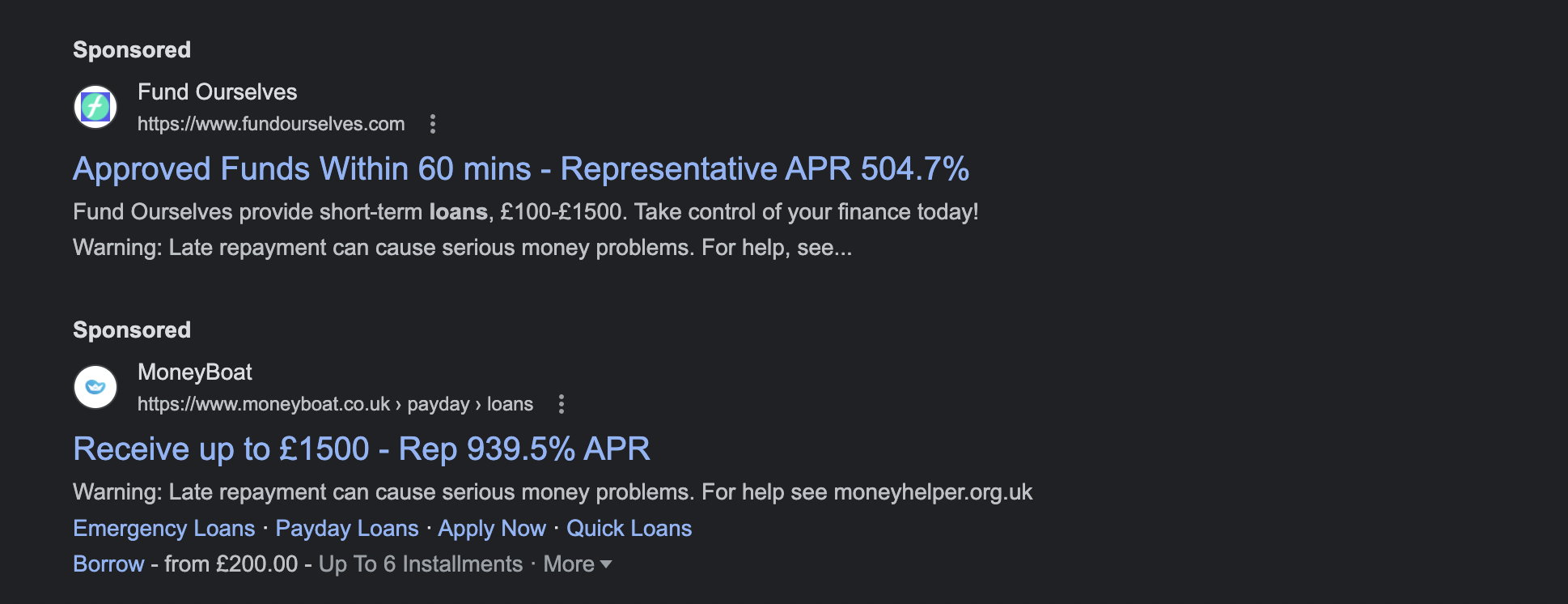

A frequent criticism of short term credit products is that they are usurious. If I type in “payday loan” into Google, I am greeted by the following results:

The offers of 500-900% APR seem extremely high. Mortgage rates are around 7% and credit cards are currently at around 20% APR. Granted, mortgages are “safer” for lenders because they are secured by real estate. But payday loans are more than 20 times as expensive than credit cards, which are predominantly unsecured too.

Is it perhaps the case that there is not enough competition in the small loans industry? Economic theory states that in competitive markets, companies will lower their prices in order to attract consumers. But policymakers and academics seem to disagree. On one hand, policymakers will bemoan that the short term small loans industry offers extremely expensive loans. On the other hand, they will claim that the market is highly saturated and competitive, often making an explicit effort to limit the competition.

For instance, a 2016 report by a London borough decries that:

there has been a 94.8% increase in pawnbrokers across London since January 2010. […] Payday lending has grown rapidly in recent years as a convenient but expensive form of short-term personal credit. […] The Council considers that the proliferation of such uses can damage the function and character of town centres.

Indeed, the industry is highly competitive. So why does it remain “expensive”?

One obvious answer is the much higher delinquency rates. Customers with less-than-stellar credit history are significantly more likely to default on their loans. About 64% of payday loans get paid back on time or early, and 22% get paid back late. Meaning that 14% of loans are defaulted on, and 36% of loans are “late”. Similarly, roughly 70-80% of items pledged get redeemed at pawnbrokers. For comparison, only about 1.6% of UK credit cards have missed payments.

Another reason these loans are expensive is that fixed costs are much higher relative to the size of the loan than for other products. For instance, both a payday loan lender and a mortgage lender will run a credit check on a prospective creditor. However, while the few pounds it costs to run a credit check is insignificant compared to the size of a mortgage, it is a much higher percentage of a 100 GBP loan. Pawnbrokers have to deal with the costs of warehousing pledged items. They often also have to take losses on items which are not redeemed.

Rejection rates also impact costs. For example, lenders have to pay for the credit checks of both accepted and rejected borrowers. If you are a lender who rejects a large percentage of prospective borrowers (because they have terrible credit), you have to charge your borrowers enough to compensate for the costs incurred due to the customers you reject.

But perhaps the greatest reason why short term consumer loans are expensive is that consumers that seek out these products are not generally price sensitive. It may seem a bit counterintuitive and perhaps even callous to suggest that people who are experiencing financial difficulties do not care about the cost of credit, but this is generally the case. Customers do not usually shop around and compare offers. They value accessibility, convenience and speed over price.

Why is this? Part of this can be explained through low levels of financial sophistication. People may not even realise they can shop around for credit. In JD Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy, the author writes:

When I nearly agreed to finance that purchase directly through the car dealership with a 21-percent-interest-rate loan, my chaperone blew a gasket and ordered me to call Navy Fed and get a second quote (it was less than half the interest). I had no idea that people did these things. Compare banks? I thought they were all the same. Shop around for a loan? I felt so lucky to even get a loan that I was ready to pull the trigger immediately.

But it doesn’t matter how financially sophisticated you are if things are urgent. If you have to take out a loan to buy groceries to feed your family, you may not have time to shop around for a few hours to find a place where a 100 GBP loan costs 20 GBP instead of 30 GBP.

As a lender, low customer price sensitivity means that you compete on accessibility, convenience and availability. Before you would even consider lowering prices, you would rather:

- Increase your marketing budget: Do your customers know who you are and where to find you? How often do you remind them? Do they even know they could get credit with you?

- Relax your credit policy: What are your rejection rates? How much credit are you offering? For how long?

- Improve your onboarding & delivery mechanism: Can people easily get loans from you? How long does it take? Do they have to walk into your shop? Can they do it online on their phone?

High-cost consumer lending is highly competitive, but lenders don’t compete on price. They compete on credit policy, onboarding, product and marketing.

How do you market small consumer loans?

Gary Rivlin’s book Broke USA describes how American payday shops in the 1990s would often open in locations close to Kmart and other grocery stores. Many people frequent grocery stores, and for many, the weekly grocery shopping can be financially challenging, which benefits payday shops. Food and groceries are the single most common thing people buy using small loans.

My former employer made the news for advertising a Buy Now Pay Later credit product along with a pizza, which was relentlessly memed about on the internet. (Sidenote: Most people criticising Buy Now Pay Later for food wouldn’t hesitate to put their grocery or fast food purchases on a credit card, particularly if this means that they can earn rewards or miles. This wasn’t always the case. Thirty years ago, people had significant reservations about credit cards being accepted at Burger King. )

Many people find advertising to people who might need to buy food on credit distasteful. People often worry that lenders will take advantage of people in a moment of need. Moreover, there’s a sense that people shouldn’t have to buy essentials, such as food, on credit. But people also strongly dislike it when payday lenders advertise credit for non-essential products either. In fact, in the UK the Advertising Standards Authority explicitly bans payday ads which “condone non-essential or frivolous spending”.

People don’t like it when lenders advertise credit for essential items, such as food, but also dislike when they advertise for non-essential items, like a new iPhone or Christmas gifts. Clearly some people think lenders shouldn’t advertise at all!

Limits on advertising have been seen by regulators as a way to throttle the industry without necessarily banning it since the late 19th century. In the 1890s, the Daily Telegraph and Standard carried 18000 moneylending advertisements a year. The ongoing debate around moneylending culminated in the Moneylenders Act of 1927, which placed severe restrictions on advertising.

To this day advertising consumer credit is highly regulated and scrutinised. In many ways it remains quite antiquated too. In the US to this day a significant percentage of credit card originations happen as a result of direct mail.

Consumer lenders are generally unsophisticated when it comes to digital advertising. They mostly rely on credit brokers to bring them leads. Credit brokers will advertise to a wide audience of prospective creditors, and then pass them on to specialised lenders depending on the creditworthiness of the customer and how much the lender is willing to pay to them. A significant percentage of users leave without an offer.

What are the trends in small consumer loans?

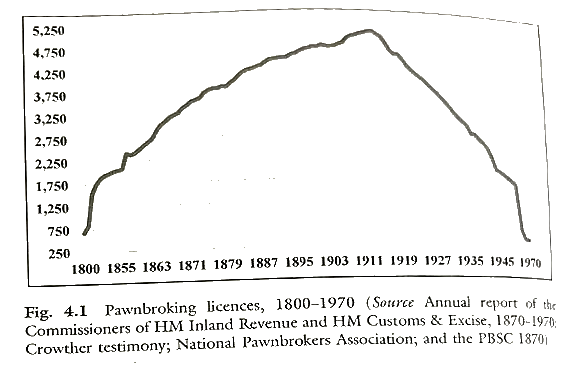

Craig McMahon’s Taming the Fringe shows that pawnbrokers started to decline with the first world war (total war tends to lead to full employment). The slow decline continued, until it accelerated in the 1940s and 1950s. Note that the 1927 act restricting advertising had little impact on the trend.

Why? The most likely explanation is the post-war expansion of the British welfare state and the creation of the NHS. This is supported by the fact that most recently, the generous government subsidies during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA (also known as ‘stimmies’) also caused a period of reduced demand for American pawnbrokers and moneylenders.

Don’t worry too much about the impact of COVID-19 on pawnbrokers and moneylenders though. Many publicly listed companies (such as FirstCash Holdings, H&T Group, Ramsdens Holdings) are now close to their all time high share price.

Are small loans usury or a legitimate business?

Demand for high cost of credit products, such as small loans, depends to a great extent on the relative wealth and welfare of a society. Governments which are concerned with the proliferation of pawn shops on high streets would do better to tackle the underlying cause of deprivation (for example, by reducing record high tax burdens) than to restrict and ban lenders.

Regulation does have an important role to play though. Because lenders don’t compete on price, legally enforced interest rate caps in the style of Hammurabi can help market participants stay within reasonable bounds (optimal caps are likely much higher than most people consider “fair”). Borrowers are often vulnerable individuals with little financial sophistication. Without the right legal and incentive structure in place, lenders will easily take advantage of them. Late fees and compounding revolving credit for instance, generate a perverse incentive for lenders to deliberately overlend. Gary Rivlin’s book chock-full of 22 year olds becoming fabulously wealthy after setting up payday shops in the 1990s and 2000s. I highly doubt they were all ethical businessmen.

Small loan providers such as credit card companies, pawnbrokers or payday lenders fulfil a legitimate need. Just ask JD Vance. It isn’t nice to have to take out an expensive loan to buy groceries or to pay the heating bill. But it beats seeing your children go hungry or cold.

Sources & Further Reading

Most of the information in this essay comes from sources that I have not referenced appropriately. The books I read while researching the topic are:

- Carl Packman - Payday Lending: Global Growth of the High-Cost Credit Market

- Craig McMahon - Taming the Fringe

- Gary Rivlin - Broke USA

- UK Competition Authority’s Payday Loan Investigation