The Tulip Craze Conspiracy

Have you heard of the Dutch Tulip craze? If so, you’ve likely fallen victim to centuries old propaganda. The Dutch tulip bubble of the 17th century never actually happened, at least not the way it is understood in popular culture.

The popular understanding of the tulip craze goes as follows:

Between 1634 and 1637 Dutch people were engaged in a speculative fever, whereby a wide cross-section of Dutch society gambled on the price of tulips. Peasants who speculated correctly on the price of tulips ended up wealthier than lords. At some point in February 1637 people realised that tulips were actually worthless and the resulting crash tanked the economy.

A popular example of this is from ‘On the Madness of Crowds’:

The rage among the Dutch to possess [tulip bulbs] was so great that the ordinary industry of the country was neglected, and the population, even to its lowest dregs, embarked in the tulip trade.

Lets debunk this propaganda:

“Everyone, from rich to poor speculated in tulips”

Only a select social circle of mostly wealthy individuals were trading tulips. These are the same individuals who also traded in art (Rembrandt was very popular at the time) as well as other “exotic” goods, such as sea shells from all over the world. They were mostly literate intellectuals, merchants or craftsmen.There is no record of “ordinary” being involved in this trade, much less people at the very bottom of society. This makes a lot of sense once you understand how tulips were traded: given that tulips needed to be in the ground most of the year, you could only trade with individuals that both had tulips (a rare, exotic commodity) AND that you trusted. It was a small circle indeed.

“The tulip craze crashed the economy”

The tulip craze happened during the heyday of the Dutch East India company when the Dutch economy was booming. Dutch merchants were supplying Europe with highly valuable goods from China and spices from all over Asia. New York was controlled by the Netherlands. Is it really possible that a few dozen wealthy men trading tulips crashed the entire economy ? Economic records for the period are not perfect, but economic historians agree that there is no evidence of a recession. Even if there had been a recession in 1637, it is far likelier to have been caused by the Black Death.

“Once the craze was over people the tulips were quickly found to be worthless”

This is evidently not true if you consider that the Dutch economy to this day exports $4bn a year in cut flowers, most of which are tulips. Tulips were often included in wills and mentioned in court cases decades after 1637. Even 50 years after the tulip craze there are records of people buying and selling tulips for extravagant figures. Tulips never became worthless, they were always appreciated, even if they never again fetched the prices promised (but most often not paid) by collectors in a craze.

So why have these legends persisted? Most of the surviving accounts from the era were from Calvinist critics who were apprehensive about the societal change of the era. They decried a lack of morals and work ethic. What better way to illustrate that than gambling on the price of flowers? At the time merchants, traders and craftsmen were becoming increasingly powerful. Finance was becoming increasingly important, with the first ever IPO of the Dutch East India Company happening in 1602. The Black Death had changed labour relations, and ordinary people could fetch far higher wages than before.

But this legend has also survived because it is a good story. We often see ourselves in tulipmania. Our interpretation of tulip-mania says more about our speculation heavy society than anything else.

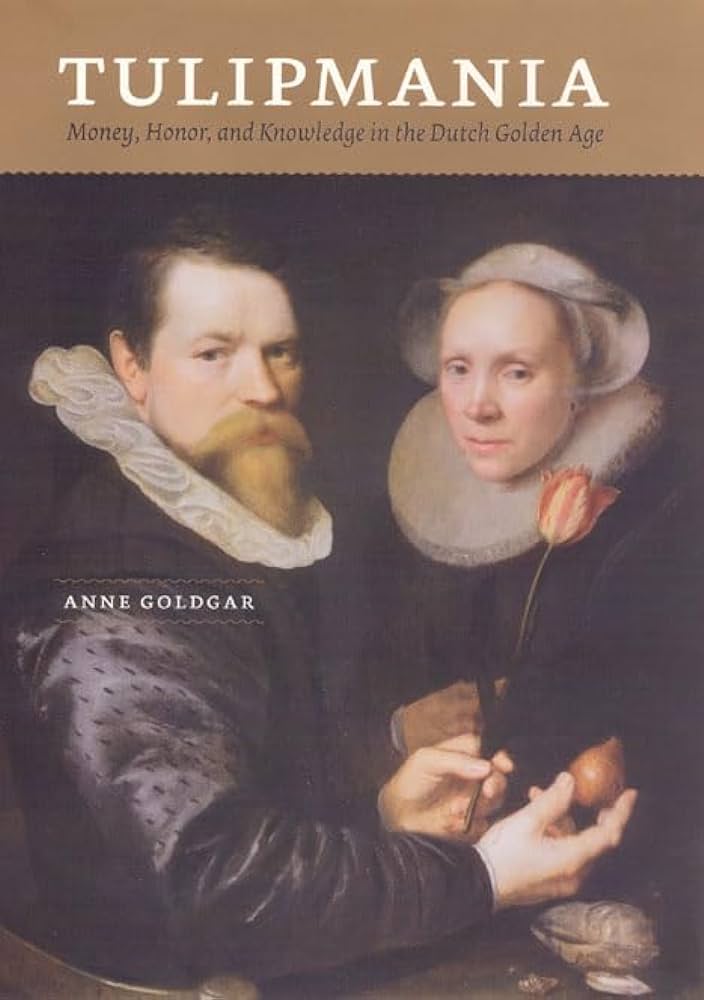

If you’d like to find out more I highly recommend Anne Goldegar’s book on the topic, Tulipmania.