From subprime crisis to the newly prime crisis

What if credit scores have misled banks into the next lending crisis? The Global Financial Crisis of 2007 is often blamed on irresponsible lending. Lenders offered large amounts of credit to “subprime” customers. Subprime being a fancy term for people with poor credit scores, who are less likely to pay the loans back.

According to Wikipedia:

The 2007–2008 financial crisis, or Global Financial Crisis (GFC), was a severe worldwide economic crisis that occurred in the early 21st century. It was the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression (1929). Predatory lending targeting low-income homebuyers, excessive risk-taking by global financial institutions, and the bursting of the United States housing bubble culminated in a ‘perfect storm’.

After the crisis, regulators and politicians implemented a wide range of rules, such as maximum loan-to-income ratios and “affordability stress tests”, to ensure lenders would be more responsible in the future. Superficially, the policy seems to have succeeded. For example, credit card delinquencies in the US remain well below the pre-2009 average (as are mortgages).

Yet the Covid-19 pandemic caused a lot of things in the economy to “break” in non-obvious ways. The supply chain crisis is often mentioned in the news and consumers have noticed shortages of everything from computer chips to eggs. In an interconnected economy, it is often hard to predict how problems will flow downstream. For instance, Ken Jarosch claimed that a shortage of microchips led to reduced production of cars, which led to reduced demand for the leather used for car seats, which led to fewer pigs being slaughtered for their hides, which led to a gelatin shortage. Gelatin is a big ingredient in gummy bears and other snacks, so there was a gummy bear shortage.

A similar story of unintended consequences might be brewing in the consumer credit market.

The stimmies

During the pandemic the US government (and many other governments worldwide) gave out generous handouts. In the USA these were colloquially known as “stimmies” and were effectively wealth transfers from the government to the consumer. FiveThirtyEight reports that:

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure, the stimulus payments moved 11.7 million people out of poverty in 2020 — a drop in the poverty rate from 11.8 to 9.1 percent. And the 2021 poverty rate was estimated to fall even further to 7.7 percent.

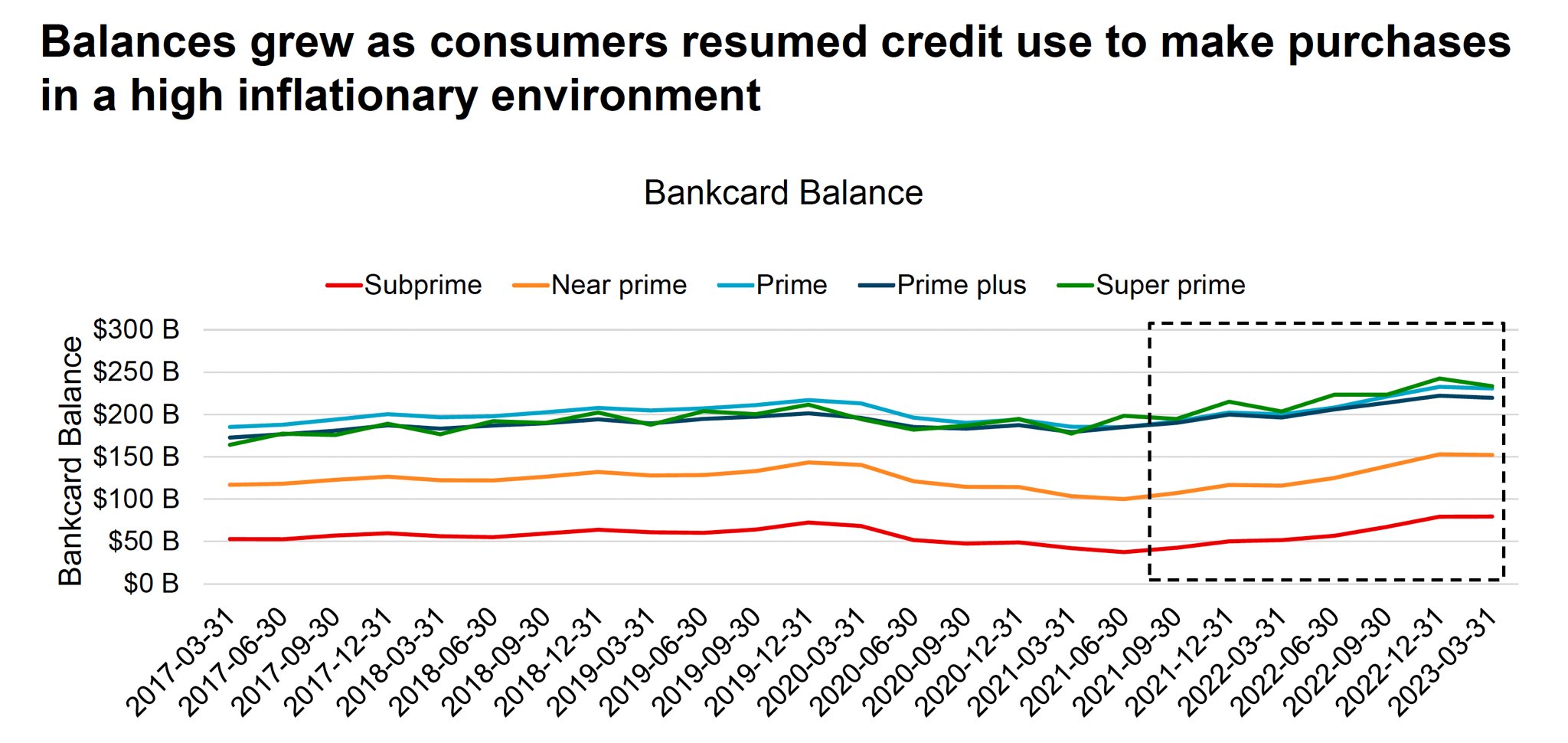

People also simply spent less because they were sat at home instead of going out to restaurants and travelling. Some people spent this surplus money on meme-stocks or crypto or NFTs. But many others simply paid back a lot of their credit card balances and other loans. In Q4 2019, consumers credit card balances at large banks were 714 USD billion. By Q1 2021 balances dropped to 566 USD billion.

This unprecedented deleveraging of consumer credit had two consequences:

- Consumer credit scores increased.

- Credit card companies started to make less money.

The combination of the two may have led to lending that was superficially responsible, but effectively disastrous.

Credit Scores & Credit Utilisation

Credit scores try to estimate the likelihood that a customer will pay back a loan. In rich countries most consumers have a credit score. Credit scores can change over time. For example, if you just turned 18 and have no credit history, your credit score is not going to be stellar. It would be irresponsible for a lender to give an 18 year old with no credit history thousands of dollars, unless it comes in the form of government subsidised student loans. But as you build up a history of good behaviour, your credit score will improve and lenders will be more willing to lend to you at their own risk. Although credit scores are a numerical value, credit analysts tend to bucket them into five categories for ease of reporting. These are from bad to good:

- Deep subprime

- Subprime

- Near-prime

- Prime

- Superprime

Every year people can transition from one bucket to another. In normal, pre-pandemic years most superprime and subprime consumers tend to stay in their respective credit score band, with quite a bit more movement in the middle categories.

The exact way in which credit scores are calculated is the “magic sauce” of the credit bureaus. But in general terms, past behaviour tends to be a good predictor of future behaviour. Credit scores usually increase when consumers pay back their loans. Moreover, when consumers pay back their loans their credit utilisation goes down. Credit rating agency Experian explains what credit utilisation is and why it is important:

Your credit utilization rate, sometimes called your credit utilization ratio, is the amount of revolving credit you’re currently using divided by the total amount of revolving credit you have available. In other words, it’s how much you currently owe divided by your credit limit […] Credit scoring models often consider your credit utilization rate when calculating a credit score for you. They can impact up to 30% of a credit score (which makes them among the more influential factors), depending on the scoring model being used. A low credit utilization rate shows you’re using less of your available credit. Credit scoring models generally interpret this as an indication you’re doing a good job managing credit by not overspending, and keeping your spending in check can help you reach higher credit scores.

In other words, consumers used government subsidies during the pandemic to pay back their loans and as a consequence their credit utilisation went down. This led to an unprecedented inflation in credit scores. People were less likely lose to credit score points, and much more likely to gain them. As this report from the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau explains:

The improvements in consumer credit scores during the pandemic were driven by consumers with deep subprime and subprime credit scores, but consumers in every credit score tier were more likely to transition to a higher tier and less likely to transition to a lower tier than before. Notably, the falling share of consumers with deep subprime and subprime credit scores was not only due to transitions out of these tiers, but also because of reduced rates of transition into these tiers.

As a consequence the median credit score of credit card account holders went up, peaking at 768 in Q2 2021.

Revolvers

Sam Colt, the man who first mass-produced revolvers, had a slogan that has since become a popular saying:

God created men, Col. Colt made them equal

Sam Colt may have made men equal in the western frontier, but to credit card companies not all customers are equal. Like Sam Colt’s customers, credit card companies much prefer “revolvers”. Revolvers are customers who carry balances over from one month to the next and pay interest on it. About half of credit card holders are revolvers. They generate the vast majority of credit card companies’ revenue.

The Federal Reserve recently published a paper claiming that credit card rewards are a wealth redistribution programme from the poor and uneducated revolvers to the wealthy & educated non-revolvers to the tune of $15bn dollars a year. A game of Russian roulette, where the winners always are the credit card companies and the financially savvy.

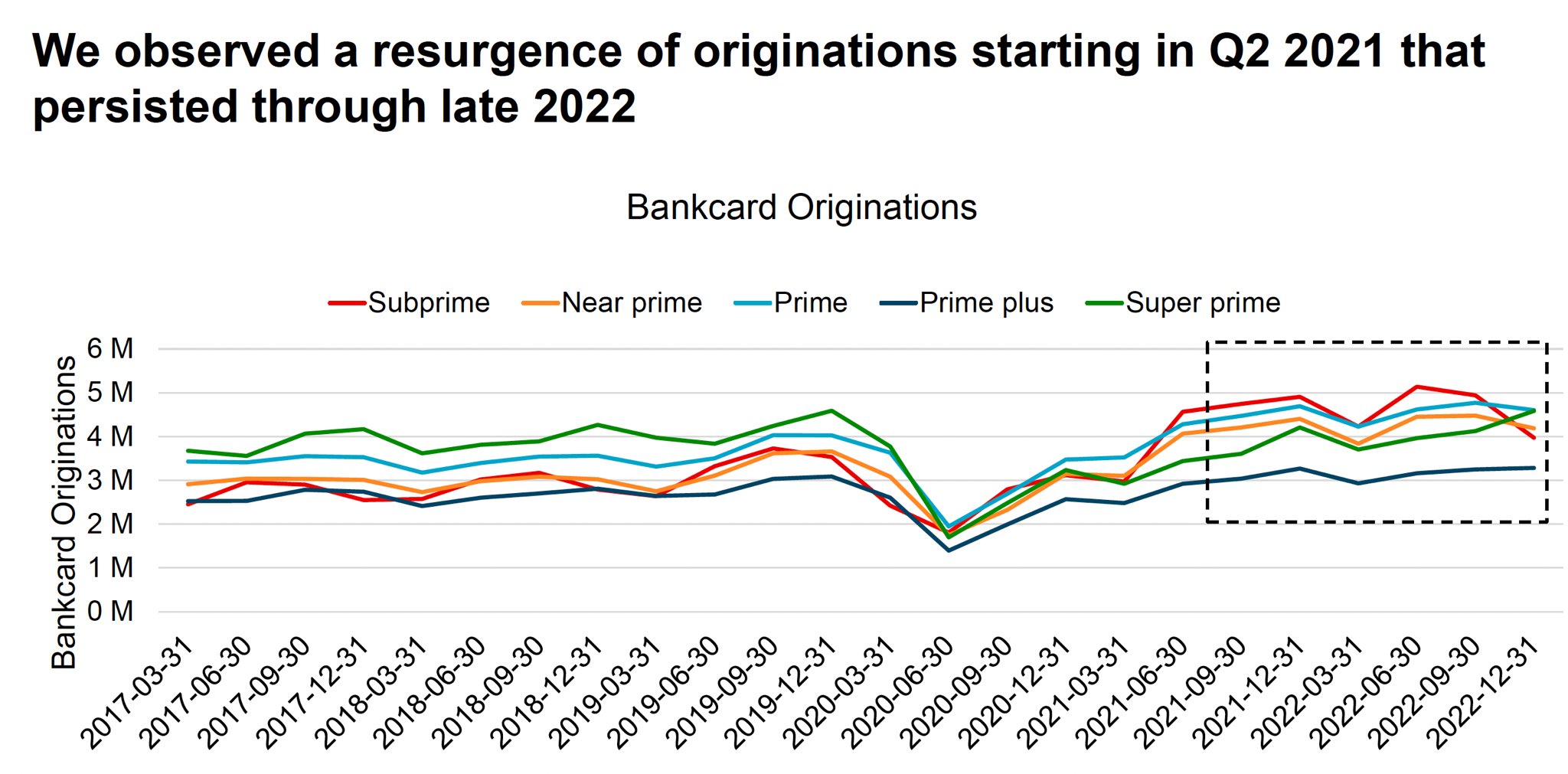

Given that credit card companies largely depend on interest income, if credit card balances go down so does their revenue. To compensate for the decline in revenues, credit card companies started issuing more and more cards during the pandemic. TransUnion, another credit bureau, reports that there was a strong uptick in originations from Q2 2021 till late 2022.

By 2023 credit card balances recovered. Thanks to regulation and more responsible lending credit card companies didn’t get carried away this time. Most of the credit card balances sit with customers that have “prime” credit scores or better. Seems like lenders avoided irresponsible levels of subprime lending this time.

What goes around, comes around

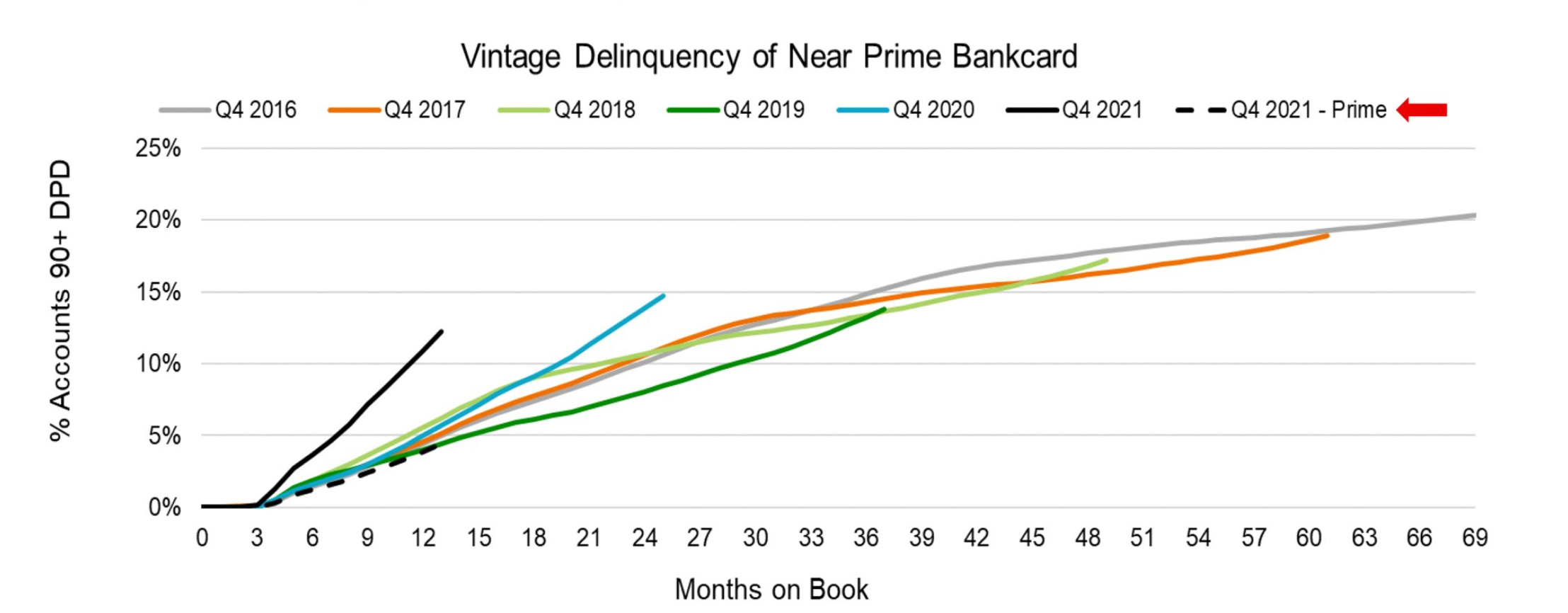

Yet there’s a problem. The performance of the 2021-2022 cohorts of loans are shocking. The performance of these cohorts was almost immediately much worse than the previous years. For example, for near-prime customers with only 12 months on book, the Q4-2021 cohort has more than double the level of delinquencies than previous Q4 cohorts.

The scariest bit for lenders is that prime customers are going delinquent at the rate of historical near-prime customers. Most of the 2021-2022 credit originations by volume was in the prime segment. These are the customers that are supposed to be reliable. Current credit card delinquency rates are an issue because they suggest that lenders fundamentally mispriced a large cohort of borrowers in 2021 and 2022.

The credit models that underpin credit scores were not calibrated for unprecedented government subsides.

God created men, the stimulus check made them equal

One-off government wealth transfers were weighted the same as regular wealth increases. Credit officers of course understood this, but there was tremendous pressure in 2021 and 2022 to issue new loans. Consumers now have to pay the highest credit card interest rates in three decades and endure record inflation.

Paradoxically, the ability to charge higher interest rates quickly can offer some protection to credit card issuers from the higher delinquency rates (at the cost of the consumer). But not all lenders can raise interest rates for customers acquired in 2021-2022. And what else did these “newly prime” consumers buy on credit?

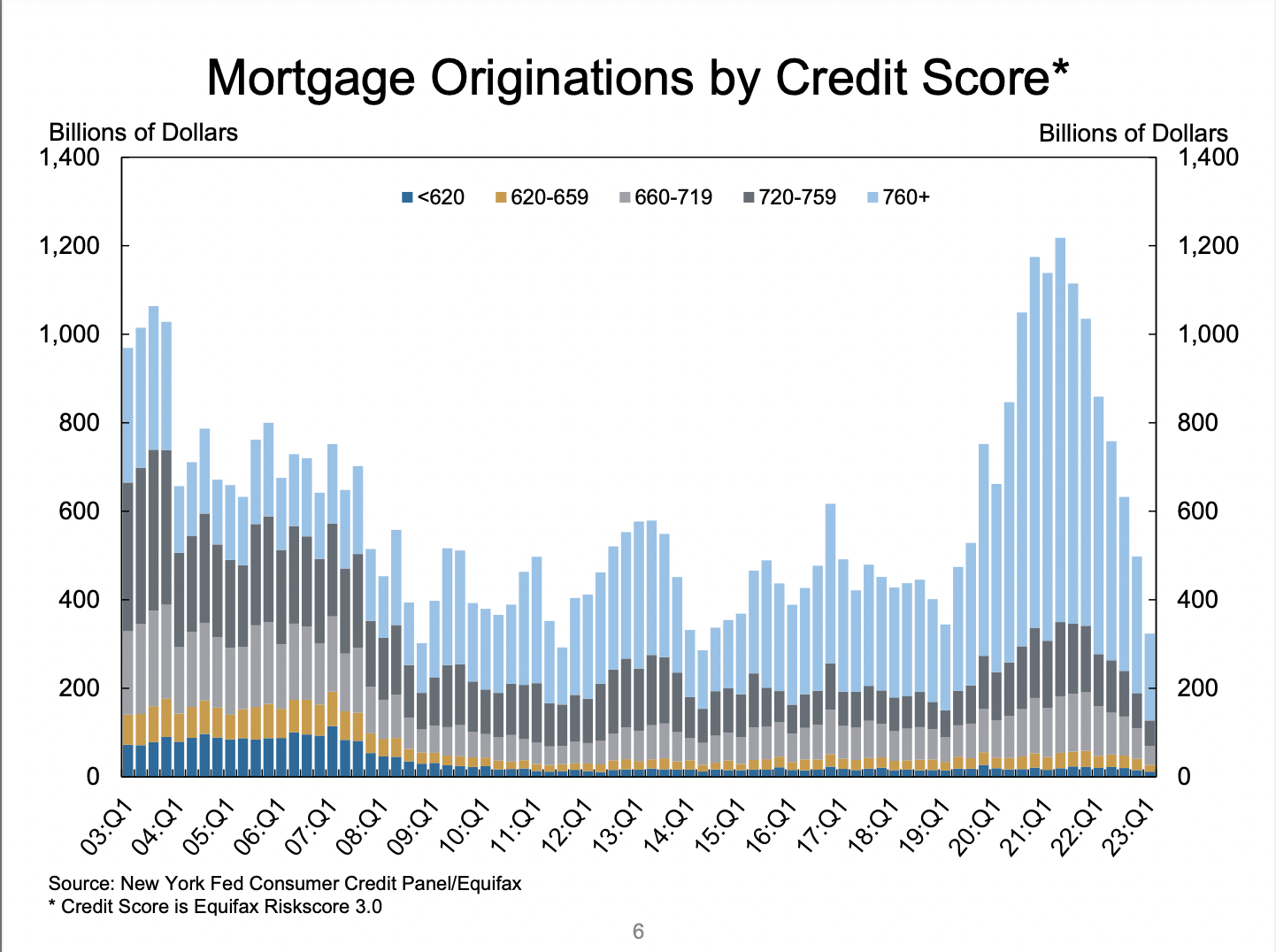

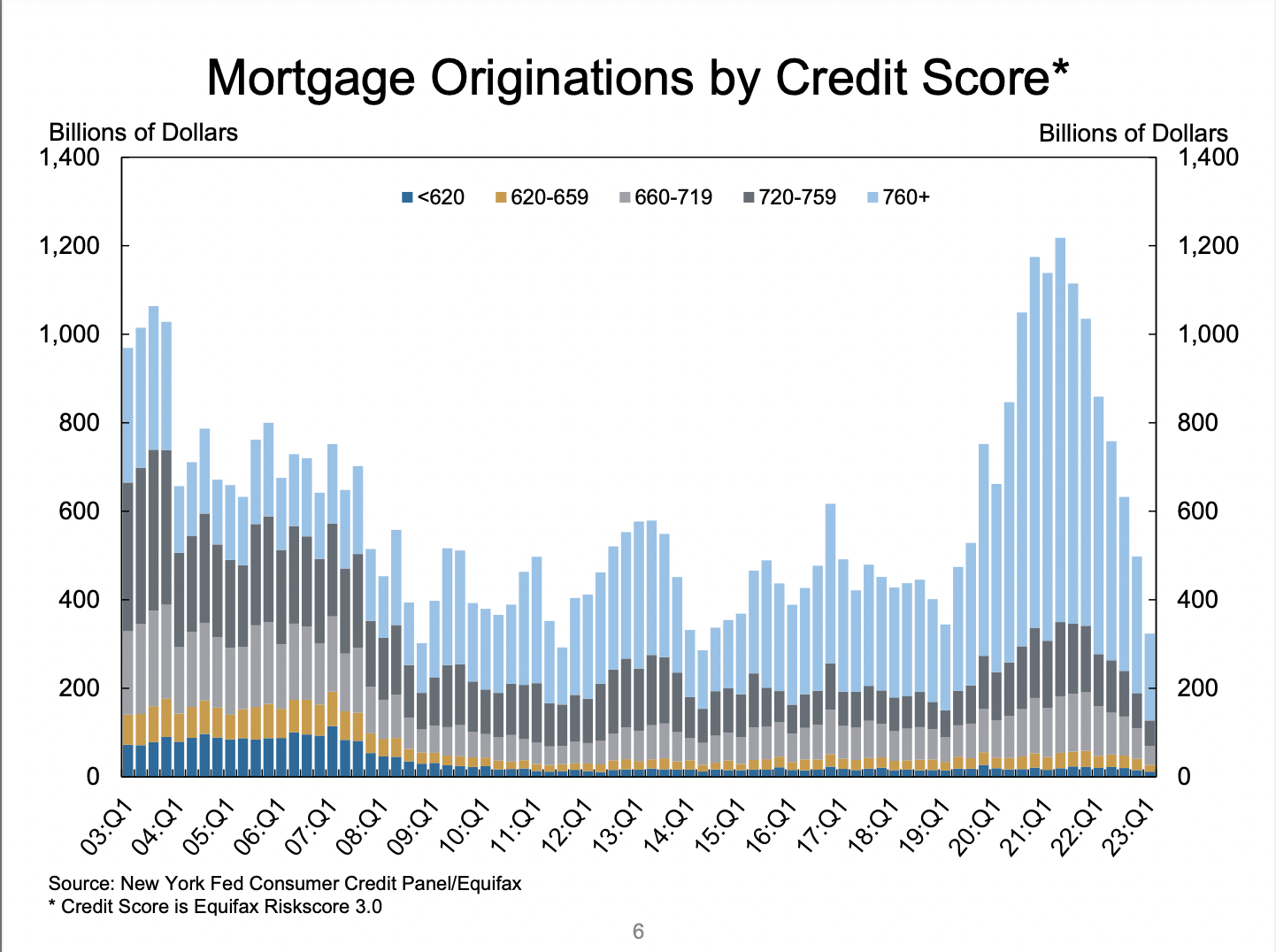

Mortgage originations in 2021 and 2022 were at levels not seen since the 2008 financial crisis. Auto loans originations also hit record highs. The vast majority of it went to “prime” customers, with unprecedented amounts of mortgages taken out by the 50+ cohort. How many of those were “newly prime”?

Mortgage lenders cannot generally raise interest rates as quickly as credit card companies, as consumers usually lock in fixed rates. In the US mortgages are fixed for 30 years thanks to government subsidies (this doesn’t make rates risk vanish, it simply moves the risk from the consumer to financial institutions, hence the recent bank failures in the US, but I digress). But in other countries consumers are not so lucky. Highly leveraged, variable rate mortgage markets that were hot during the pandemic are likely to be impacted the most. Many consumers will find themselves struggling to pay an increasingly expensive mortgage for a property they overpaid for, using credit they would have not qualified for had it not been for the pandemic.

The “Newly Prime” Crisis?

In this post I mostly focused on credit card data from USA because there is good data available and credit cards tend to show signs of trouble earlier than mortgages, but similar trends are happening worldwide. Conventional credit models had no way of accounting for the COVID-19 pandemic and lenders were under significant pressure to issue more loans in 2021. As a result, they issued large volumes of cheap loans to people they wouldn’t have lent to just a few years before.

If the risk of defaults in consumer credit markets is being significantly underestimated, the global economy might be in for a nasty surprise. And keep in mind that the current shocking performance of the 2021-2022 vintages comes during a time where the labour market is tight and unemployment is low. The strength of the labour market is in large part due to a large number of boomers who didn’t return to the labour force after the pandemic. Should the labour market start showing signs of weakness, the hot real estate markets of 2021-2022 will be under significant pressure.

Credit drives the global economy. If lenders pull back due to unexpected losses, consumers will spend less on goods, cars and houses. The increase of interest rates has already made life difficult for many lenders. So far most negative impacts on the delinquency side have been masked by a tight labour market and strong consumer spending (both likely due to newly retired boomers).

In the US student loan repayments are due to restart in October 2023. The pause on student loan repayments was a significant subsidy to consumers, particularly for the young, newly prime consumer who got a mortgage in 2021/2022. Auto loan delinquencies for the 18-29 cohort is already at levels not seen since 2009. Once student loan repayments are restarted consumer spending will take a hit. Delinquencies will increase.

None of this is news to credit analysts. The question is, have the second and third order effects been priced in yet?