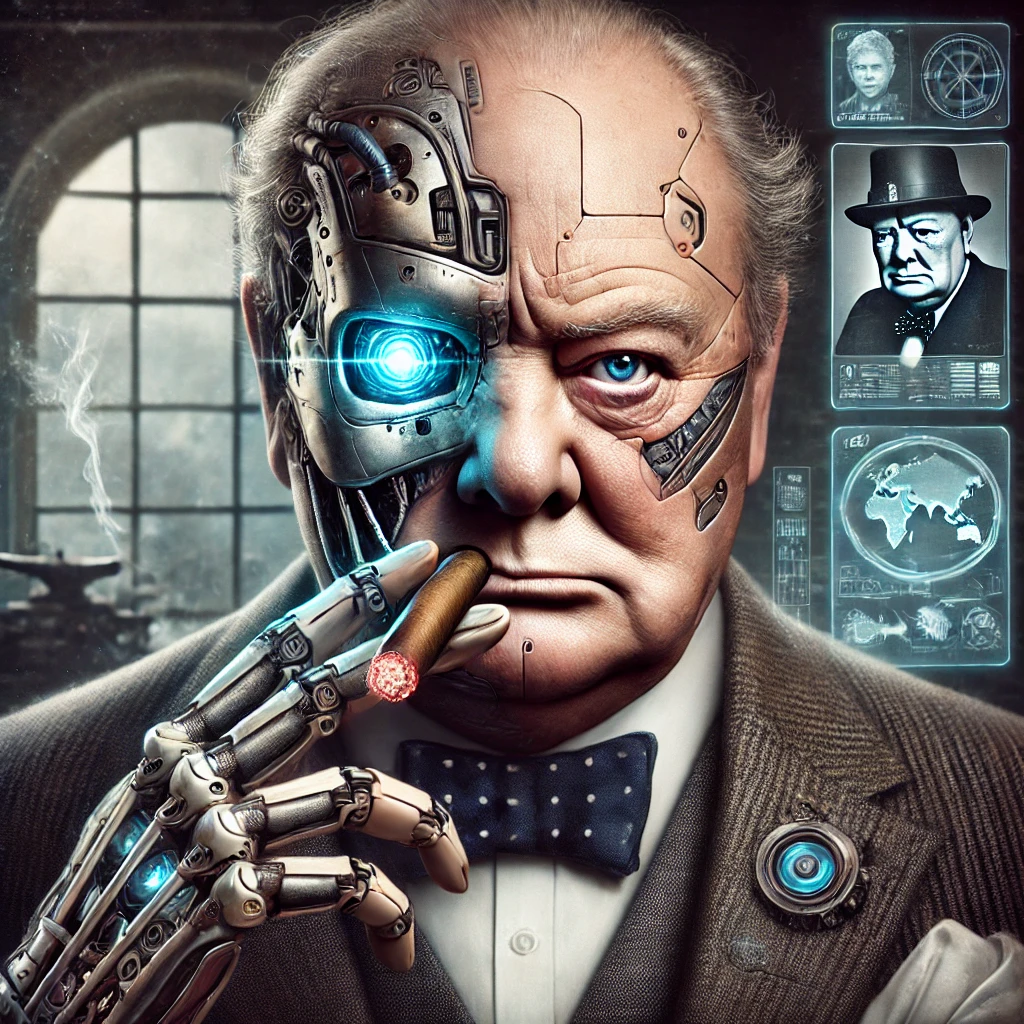

Unleashing my inner AI Churchill

Upon turning 31, I felt naturally compelled to begin reading Churchill’s biography. While Churchill is remembered for many things—his heroic leadership during World War II, his ever-present cigars—he’s also remembered as a prolific writer. During his lifetime, Churchill produced an enormous volume of works: books, histories, and autobiographies. These not only supported him financially during his political career but also cemented his legacy as a historical figure.

What’s particularly interesting about Churchill’s writing process is that he rarely wrote in the way most of us do—sitting at a desk, typing or writing by hand. Instead, Churchill primarily wrote through dictation. He would speak his thoughts to secretaries who would transcribe them, after which they would collaboratively edit and refine the text. This method enabled him to produce an astonishing amount of written work.

While I cannot afford a personal secretary, I now have access to large language models. Though these AI tools may not yet be perfect for many applications, they serve admirably as digital secretaries. They can take my dictated thoughts and transform them into coherent essays. Will the result be perfect? Probably not—but then again, neither were Churchill’s human secretaries. Serious editing is still required, whether the secretary is human or not. This technology has democratised a writing method that was previously available only to those who could afford personal staff.

Does this mean I’ll become as prolific a writer as Churchill? Also no. But it’s worth noting that this technology has unlocked a writing approach that was previously inaccessible to most of us.

Before fully embracing my inner “AI Churchill,” however, there are several considerations to address. First, I wonder if Churchill ever worried whether the words published under his name were truly his or those of his secretaries. I suspect he didn’t fret much about this, as it was ultimately a collaborative process rooted in his original dictation. He was famous for painstakingly reviewing every single line. However, my situation differs slightly: Churchill’s secretaries were, like Churchill, likely educated individuals steeped in the works of Edward Gibbon, Thucydides, the Iliad, Virgil, and other classics. My AI secretary, while also trained on these works, has also absorbed the more dubious content of Reddit posts and YouTube comments. This raises questions about the extent to which my AI-assisted writing truly reflects my voice versus that of the internet hive mind.

Another concern is my general aversion to being edited—whether by human or AI editors. I particularly dislike when an editor decides my phrasing is too colloquial or vulgar. What makes this especially frustrating is that the editor is often right. Moreover, I believe good writing is fundamentally an exercise in clear thinking. The process of crafting and refining sentences helps clarify exactly what I want to say, and this is what I find most enjoyable about writing. If I delegate the editing and refinement to AI, I worry I might miss out on this crucial thinking process, ending up with polished essays but fewer original thoughts.

Nevertheless, I’ve decided to embrace the AI secretary approach for one compelling reason: I have dozens of half-written or unwritten essays languishing in various states of incompletion. Some of my most successful pieces—essays that have connected me with friends worldwide and even led to dinner invitations with former UK prime ministers (though not Churchill)—sat in draft form for over a year as I endlessly polished and refined them.

Given this tendency toward procrastination, I’ve concluded it’s better to have a hundred AI-assisted essays published than dozens of perfectly crafted pieces existing only in my mind.