Mines in the Air

There is an entirely underrated opportunity with airships that challenges our conventional understanding of both lighter-than-air flight and modern warfare. If you’ve followed my thoughts before, you know I occasionally get quite excited about this topic – and I should qualify upfront that I’m no aerospace engineer, so take what follows with an appropriate grain of salt. But the possibilities here are fascinating.

While airships were common a century ago and drove much of the early progress in aviation, they have since fallen into relative obscurity. However, recent developments in the Ukrainian war suggest that airships and balloons might be poised for an unexpected renaissance—albeit in a form their original inventors never anticipated.

The fundamental appeal of airships lies in their remarkable endurance: they can remain airborne for extended periods while consuming minimal energy. This capability stems from their use of lighter-than-air gases, primarily either hydrogen or helium. Each gas presents its own unique trade-offs. Helium, while safer, offers less lift and exists as a finite, increasingly expensive resource. Hydrogen, conversely, provides superior lift but comes with a set of characteristics that have historically made it, to put it mildly, terrible to deal with.

These “terrible” characteristics are actually fascinating in their extremity. Hydrogen is literally the smallest element in existence, meaning it can seep through almost any material – metals, plastics, you name it. It’s like trying to contain a ghost made of the universe’s tiniest escape artists. This permeability not only makes long-term storage problematic but can also lead to hydrogen embrittlement in metal structures. Furthermore, hydrogen’s flammability characteristics are particularly treacherous: it burns with an almost invisible flame, can ignite with minimal energy (about one-tenth that required for gasoline vapor), and has an exceptionally wide flammability range in air (4-75%). These properties contributed to historical disasters like the Hindenburg, pushing the industry toward the safer but less efficient helium.

But here’s where things get interesting: what if these seemingly problematic characteristics could be transformed from liabilities into tactical advantages? This paradigm shift is particularly relevant in the context of modern warfare, where the Ukrainian conflict has demonstrated the revolutionary impact of drone technology. Current drone warfare faces two significant limitations: restricted flight time due to battery constraints, and limited range, particularly for the smaller, multi-propeller drones that have become ubiquitous in tactical operations.

Enter the concept of the weaponized hydrogen balloon—a synthesis of historical lighter-than-air technology with modern guidance systems. The very properties that make hydrogen problematic for civilian aviation could make it ideal for military applications. Its high flammability becomes a feature rather than a bug, essentially creating a dual-purpose weapon: the lifting gas itself is explosive, and the platform can carry additional incendiary or explosive payloads.

The economics of this approach are particularly compelling. Hydrogen is dirt cheap to make from water through electrolysis. The balloons themselves require little more than basic plastic fabrication. Even the weight regulation system can be as simple as water bottles for ballast – there’s evidence of exactly this being tried in Ukraine right now. When combined with minimal guidance technology, the result is a remarkably cost-effective weapons platform—perhaps as little as $5 worth of materials capable of threatening multi-million dollar aircraft.

The strategic implications are significant. Those “nightmare” properties of hydrogen suddenly become perfect for warfare. That invisible flame? Good luck spotting these threats with traditional detection systems. The fact it seeps through materials? Perfect for ensuring the whole thing goes up when it hits something. Its hair-trigger flammability? Exactly what you want in a weapon.

A nation without air superiority, or even a relatively unsophisticated military power, could theoretically deploy thousands of these hydrogen-lifted devices. Such a swarm could serve multiple purposes: direct attacks, area denial, or simply forcing enemy aircraft to operate at suboptimal altitudes to avoid collision risks. This approach effectively creates an aerial minefield—extending the principle of denied areas from land and sea into the air domain.

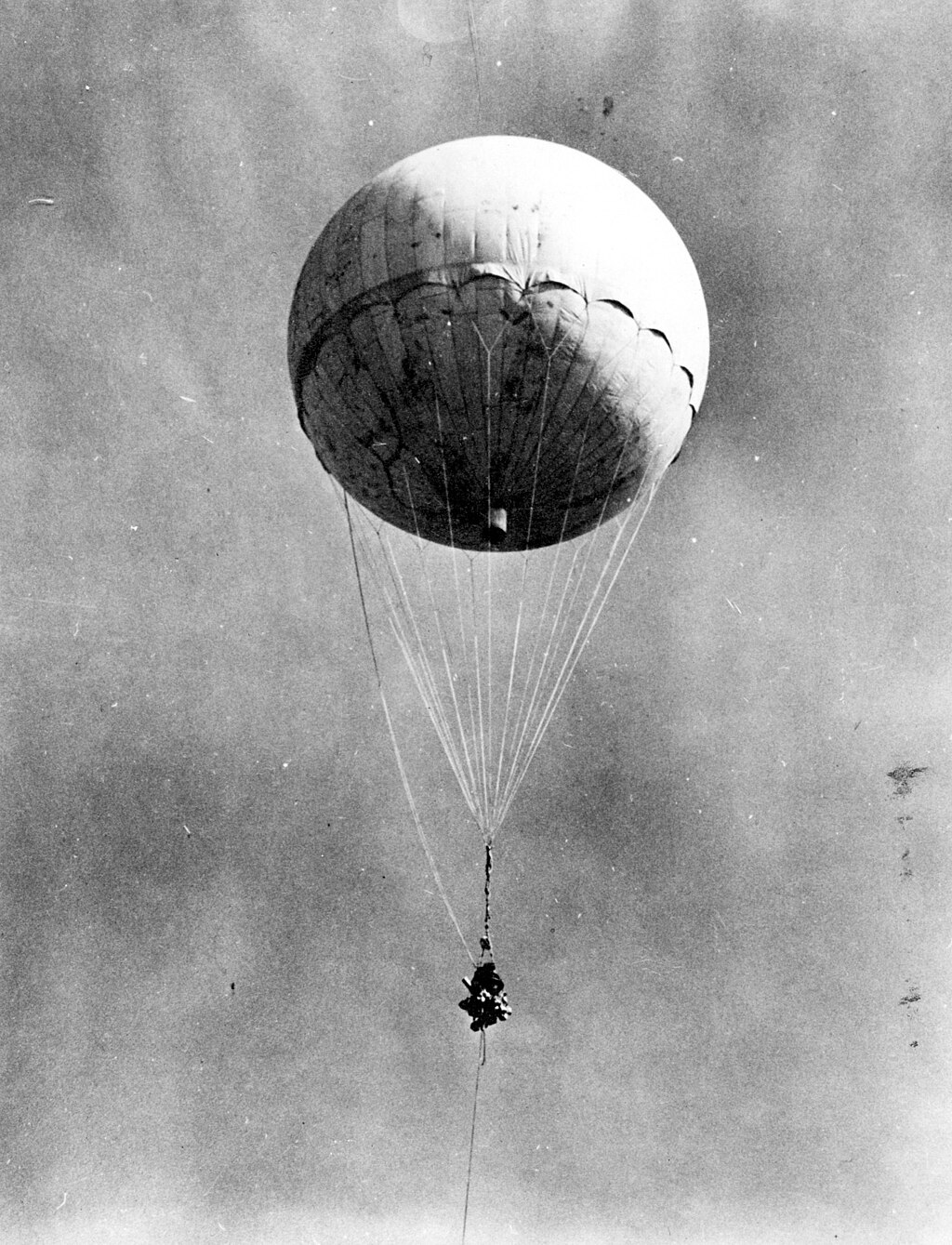

This concept draws inspiration from historical precedents, such as the Japanese Fu-Go balloon bomb campaign of World War II, but with modern technological enhancements. While the Japanese campaign achieved limited success due to primitive guidance systems and the vast distances involved, today’s GPS and remote guidance capabilities could transform such platforms into precise, controllable weapons.

What we’re witnessing might be the emergence of a new form of asymmetric warfare. Just as naval mines allowed smaller nations to challenge major naval powers by denying them freedom of movement at sea, hydrogen-based aerial platforms could potentially democratize the air domain. The combination of low cost, extended loiter time, and inherent explosiveness creates a unique weapon system that could fundamentally alter aerial warfare calculations.

Is this the future of aerial warfare? We’ll see. But the convergence of historical technology with modern guidance systems, coupled with hydrogen’s unique properties, suggests we might be on the cusp of a significant evolution in military aviation. Sometimes the worst tool for one job turns out to be the perfect tool for another – you just have to change how you’re looking at the problem.