The Migrant Crisis and Demography

In September, images

of anti-riot police in a standoff with desperate migrants were shown on television, inspiring many people to volunteer and even more people to chatter about the situation.

Yet the problem with our handling of crises is that we often wait for one to happen before doing anything (even just notice something is amiss).

Humans are vulnerable to overlooking gradual phenomena

with no easily distinguishable onset.

There is an ongoing global demographic transition and it will influence most shifts in the next 25 years, be it in politics, business or international relations.

The global population pyramid is turning into what demographers call an onion. While population growth continues and the global population is predicted to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, growth rates are slowing and there is a vast divergence between geographic regions. For instance, half the population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa whereas Europe’s population is expected to decrease. Moreover, increasing longevity and decreasing fertility mean that the population aged over 60 is fastest growing (expected to go from 0.9 billion to 2.1 billion by 2050). Since the dawn of civilisation the global population has always been young and growing. This is no longer the case.

To feed the burgeoning developing world food production must increase until 2095 when fertility levels converge to replacement level. A failure to do so could lead to unprecedented famines. In the developed world political pressures raised by the care of the elderly will step into the limelight. By 2050 the number of workers per retiree will drop to below 2 in 35 (mostly European) countries. It is not difficult to concieve how this may lead to animosity within the working force in countries with significant wealth redistribution. On the other hand, China, traditionally reliant on familial support, faces the risk of millions of elders falling outside safety nets. Moreover, the economic and demographic asymmetry between the developed and the developing world will become an increasingly powerful driver of migration, much to the chagrin of politicians like Viktor Orban. Politically, we must be prepared for an inter-generational conflict with a multicultural twist.

Businesswise, companies are scrambling to provide for the growing population of the developing world to make up for declining consumption in developed world.

More worryingly, consumer behaviour in the developed world is changing beyond what would be expected from demographic changes.

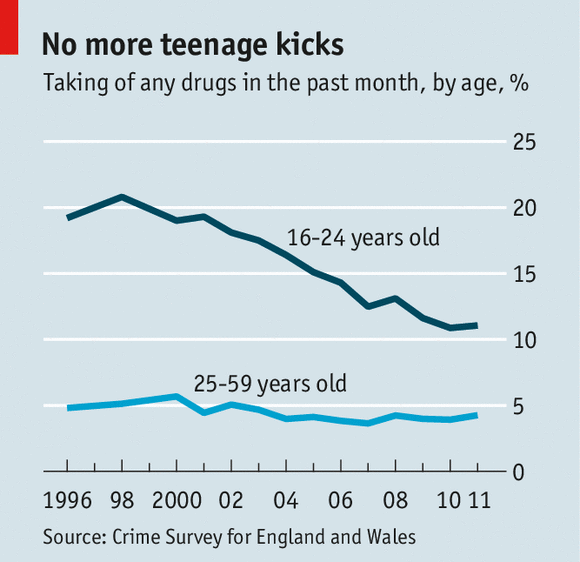

Statistics show young people today are quite unlike young people in the 1970’s: much less drugs, sex and rock-and-roll (and cars, disposable income and alcohol).

The businesses of tomorrow must either latch onto the growth of developing countries or to growth areas of the developed world (such as healthcare).

To ensure peace and prosperity we must be prepared to adapt to this new reality. Above all, leaders must recognise that mass migration, in one way or another, is likely to be inevitable and efforts should be made to soften cultural and intergenerational shocks. For instance, wealthy aging countries could sponsor schools in young poor states which would act as a funnel for well-educated immigrants with the relevant language skills. Much more can be learnt from states with experience in immigration (such as the United States). Only then might we avoid the most dramatic images on television today.

Graphs shamelessly stolen from The Economist