Reading Las Casas: A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies

Columbus landed in the New World in 1492. By the 1520s—barely thirty years later—the Spanish had established significant colonies across the Caribbean and devastated entire indigenous populations. I knew the conquest was fast, but I hadn’t fully grasped just how fast. Within less than a century, European powers had conquered the continent.

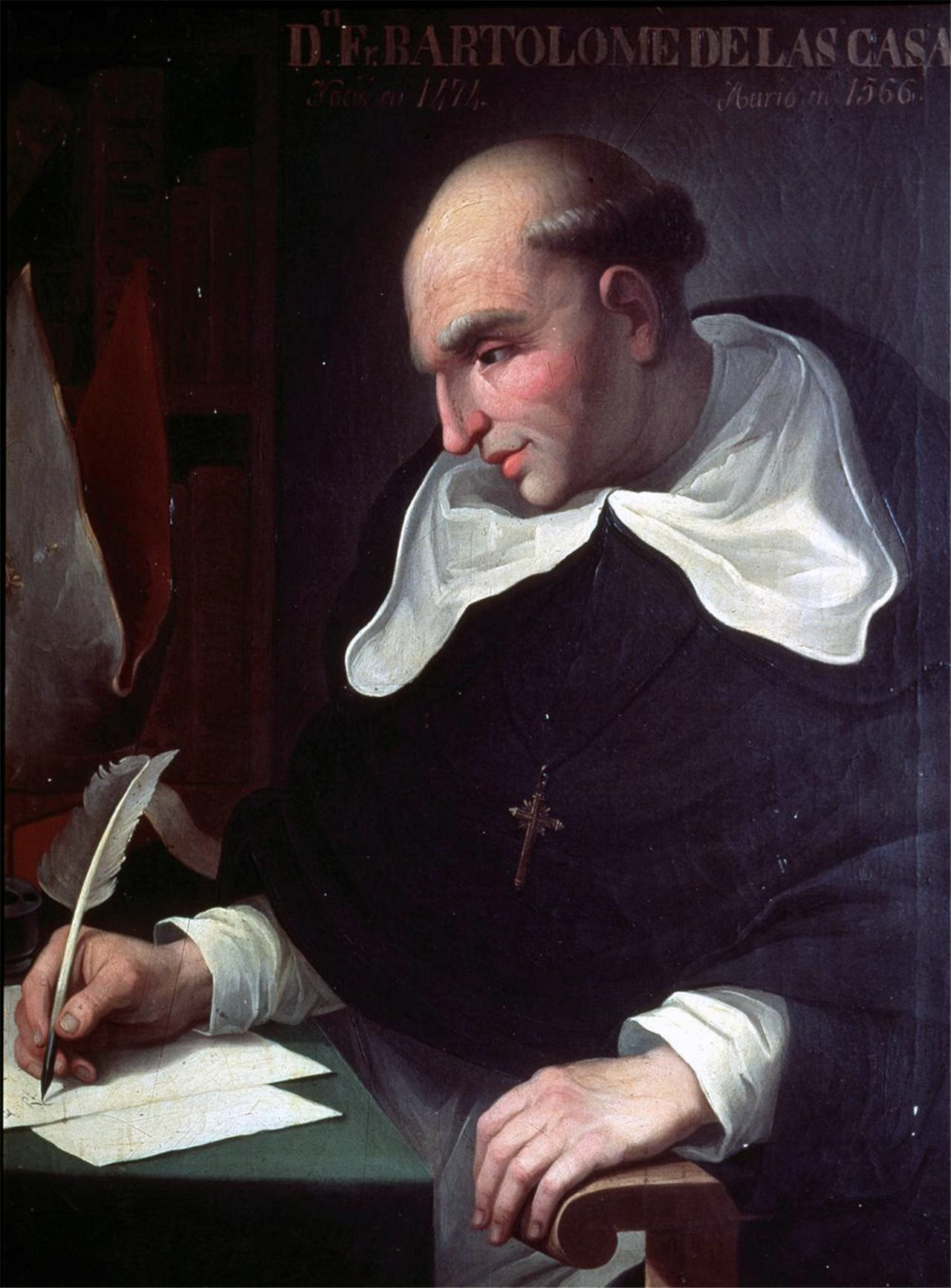

Bartolomé de las Casas’s writings are some of our primary windows into this period. Las Casas was a Dominican friar who spent decades in the Americas and became one of history’s earliest human rights advocates. A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1552), written as a plea to the Spanish Crown, catalogues atrocity after atrocity committed by the conquistadors against indigenous peoples.

Las Casas is the closest we get to a pro-indigenous perspective. Here lies the problem with studying this period: we have almost no unfiltered indigenous perspective. The vanquished left few written records. Las Casas was the closest we get. We have Cortés writing his promotional letters to the King. We have Las Casas writing his histories. But the voices of those who experienced the conquest from the other side are largely silent.

Las Casas is unquestionably a moral figure. His willingness to criticise the brutality of his own countrymen, at considerable personal risk, was remarkable for his time. But he was also a man with a political agenda. He wrote A Short Account specifically to persuade the king to implement reforms protecting indigenous peoples. This purpose shapes everything he writes.

The chapter on the conquest of New Spain (Mexico) illustrates the issue with this. You don’t have to believe everything Cortés wrote to recognise that indigenous peoples played an active role in the defeat of the Aztec Empire. According to Hugh Thomas’s comprehensive history of the conquest, and Matthew Restall’s When Montezuma Met Cortés, Cortés and his small band of soldiers were actually a minor component of the forces that conquered Tenochtitlan. The Spanish managed to build a massive coalition of indigenous allies who battled alongside them against the Aztecs.

Why? Because the Aztecs were hated. They were brutal imperialists themselves, conquerors who extracted tribute and sacrificial victims from subject peoples across Mesoamerica.

But this doesn’t fit Las Casas’s argument. He portrays the Aztecs, like all indigenous peoples in his account, as docile, gentle, and servile—people who would make excellent Christians and loyal subjects of the Crown, if only the conquistadors would stop murdering them. This was his thesis: that Spanish cruelty was not only morally wrong but also counterproductive to the Empire’s interests. It’s a clever argument, but it flattens the complex political reality of pre-Columbian America into a simple morality tale.

This isn’t a criticism of Las Casas so much as a recognition of what we’re working with. He is one of the few sources we have for this period, and he wanted to achieve something political at the Spanish court.

Reading Las Casas has left me wanting to explore more primary sources from this period. He mentions fascinating figures like Pedrarias Dávila, known as “the Wrath of God”, a supremely interesting and evil character who was shipped out to the Americas in his seventies and ruled with an iron fist for twenty years. He also discusses the deportation of indigenous peoples to the mines of Peru, a massive forced migration that reshaped the continent’s demography.

There’s potentially much still to be discovered. Given how quickly these populations were decimated, there may be significant archaeological findings waiting in the areas where indigenous communities were destroyed. The speed of the collapse means that much may have been preserved—material culture frozen in time by catastrophe, waiting for future researchers to uncover and interpret.

For now, Las Casas remains essential reading, not as an objective chronicle, but as a passionate moral document from a man who witnessed horrors and tried to stop them. The fact that his account is politically motivated doesn’t make it less valuable. It simply means we must read it for what it is: one voice from a period that desperately needs more.